CULTURE & ENTERTAINMENT

Race and Art in the Church

By Cory Carwile

Christianity has borne a staggering amount of art in its nearly two-thousand-year history. From painting to sculpture to architecture, biblical stories and characters have provided consistent inspiration for western artists of all types. One might notice, though, that in art from Europe and North America biblical characters are almost always portrayed as being white/European. Indeed, because of the vast amount of Christian-themed art produced in Europe, it can look like Christians think of the biblical characters exclusively as white Europeans. This is especially noticeable in artistic portrayals of Jesus, who, particularly since the Renaissance, is nearly always portrayed as a well-groomed white man. What implications might we draw from this tendency in art history? Are there racial implications to this ethnic re-imagining of Christ and other biblical characters? Is this portrayal meant to convey some sense of white superiority over other races? Why change the portrayal of Jewish characters, particularly when the ethnic Jews — the genetic descendants of Israel — have such a special role in the biblical narrative?

To be clear, God holds all ethnicities, genders, and nationalities in equal dignity and importance. In the book of Galatians, the Apostle Paul clarifies that the Christian's identity is found in Christ, not in any particular ethnic background or nationality: "For all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Galatians 3:27, 28). In the book of Revelation, God is described as welcoming into His kingdom people from all nations, tribes, peoples, and tongues (Revelation 7:9; 5:9). No special allowances are made for any specific people group. In Genesis 1, the human race is described as being made in the image of God; this is an honor bestowed on the entirety of humanity, not to any specific subgroup of people.

It's true that God deigned to bring about the blessings of salvation through a particular family line: the sons of Israel, and more specifically still, the family line of David, king of Israel. The people of Israel were unconditionally selected by God to prefigure and inaugurate the eschatological Kingdom of God on Earth and prepare the way for the Messiah, Jesus Christ. This marked the people of Israel in the Old Testament as a peculiar people, playing a unique and vital role in God's redemptive plan for humanity. This doesn't mean that they were the only people of importance on the Earth, or that God didn't care about the rest of humanity in the Old Testament; part of the expectation for Israel is that through them the entire world would be blessed (Genesis 22:18), and in places like the book of Jonah we see God going out of His way to offer mercy and justice to other nations outside of Israel.

In the New Testament, we find that Christ has fulfilled the obligations of the Law of Moses, and believers in Him are under the New Covenant, not the Old Covenant God drew Israel into. This Covenant is not tied to a particular ethnic or people group or even law-keeping, but on sincere faith in Jesus Christ. This membership persists into the final state of humanity in the New Heavens and New Earth; nowhere in the Bible is it suggested that certain ethnicities or races will be treated as superior to the others in the New Creation. While there are varying theories about the exact role the nation of Israel, as an ethnic group, will play in the final days of history, we have no reason to think the final state of humanity in the eschatological Kingdom of God will be stratified based on race or nationality.

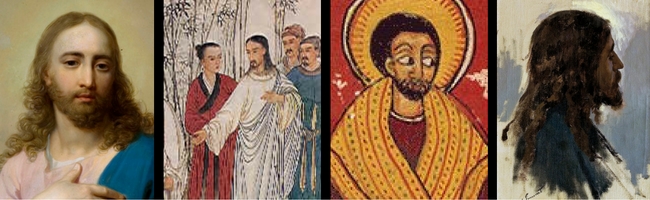

Coming back to the topic of art, we've noticed that in Western (and particularly European) art history, the characters of the Bible are consistently portrayed as white. Undoubtedly, these depictions were in many cases meant to espouse racial superiority and to downplay the roles of other ethnic groups in the Bible. That said, in many, cases these depictions are due more to the curiosities of cultural interpretation and filtration. Historically, it is not unusual for cultures to depict stories from other areas in light of the interpreting culture's own context. Put another way, artists often use their own cultural markers — including clothing, architecture, and ethnicity — when portraying stories from other cultures. Many artistic representations of Bible stories in China portray the characters as Chinese or East Asian. Much of the Church art in the Ethiopian church in Africa portrays biblical characters as African. In all these places, as well as in Europe, biblical characters are portrayed as wearing clothing contemporary to the time of the artist and surrounded by contemporary architecture. This is true even outside of religious contexts; the Arabian story of "Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp," for instance — supposedly first told to French story-collector Antoine Galland by a Syrian scholar — is set in China, but the characters and place descriptions are all stereotypically Arabian.

These cultural retoolings may have been due to a sense of cultural or racial superiority on the part of the artists, but it may have been informed just as much by a dearth of knowledge about the culture the story comes from. How does one portray characters from another culture when one knows nothing of how those people looked and dressed in the time of the story? In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, when knowledge about distant times and cultures was informed, at best, through writings and oral, artists filled in the blanks in their knowledge (such as aesthetic and ethnic appearances of those cultures) using what they knew, i.e., their own culture.

The racial re-imagining of biblical characters (and especially of Jesus) by western artists has been largely harmful to the Church; the way we ingest and consider art can affect how we think about the world, and a predominantly white culture viewing the racially varied characters of the Bible almost exclusively as white people can easily engender a skewed view of the importance of white people or "white culture" in God's plan for redemption. It makes it insidiously easy for white Christians to graft the Biblical characters, even subconsciously, into their own racial identity, rather than to their Christian identity. To be clear, this isn't to say there's anything inherently evil in the Christian themed works of Caravaggio, Michelangelo, or Raphael. Such works of art are beautiful, and thought-provoking, and reflect, to an extent, the religious thoughts of their culture. The portrayal of biblical characters as white may not have been self-consciously intended to support a racial agenda. But it certainly made it easier. And though we might be more self-conscious of it in modern times, it is an error in thinking the Church has still not gotten totally past.

Thankfully, we believe in a God who make all things new (Revelation 21:15). There will be a time when our minds are renewed and we will love our neighbors properly, as God intended us to. The hope and knowledge we try to reflect when we make art will come to full fruition, and misinterpretation will no longer be a concern. For now, though, we trust ourselves to God and His revelation to us, and pray for His guidance to override the more sinful inclinations of our hearts.

Images: Vladimir Borovikovsky; "Jesus"; Public Domain

"Chinese depiction of Jesus and the rich man"; 1879; Public Domain

"Jesus Christ; Ethiopian Church icongraphy"; 17th-18th c.; Public Domain

Enrique Simonet; "Cabeza de Jesus"; 1890-1891; Public Domain

Tags: Biblical-Truth Controversial-Issues False-Teaching Jesus-Christ

comments powered by Disqus

Published 11-28-16