THE THEOLOGICAL ENGINEER

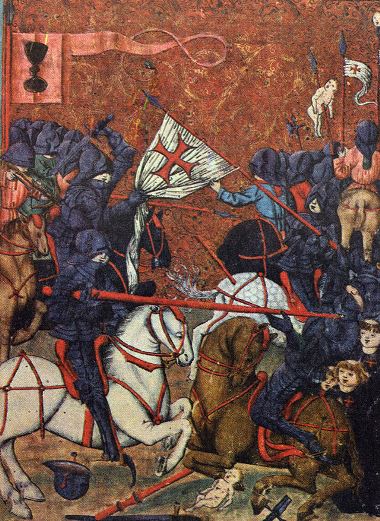

The Crusades

Faithless Fairy Tales Part 3

By Jeff Laird

Faithless Fairy Tales:

Introduction

Part 1: Galileo

Part 2: The Scopes Trial

Part 3: The Crusades

Part 4: The Spanish Inquisition

Crusades Single Page/Printer Friendly

This is the fourth in a series of articles examining how inaccurate, warped versions of real historical events are misused in order to attack Christianity. These Faithless Fairy Tales may satisfy "once upon a time" appetites, but they don't represent the truth. These are some of the more common anti-religious historical myths thrown at Christians, debunked by means of the actual storylines.

The Crusades are a particular favorite of the anti-religious or anti-Christian critic. Typically, the Crusades are described as brutal acts of atrocity, targeting innocent and peaceful Muslims in a racist, zealous religious war aimed at forcibly spreading Christianity. This view is not just a caricature, it's blatantly false. A parallel error would be describing US military action in the Pacific as an effort to forcibly convert people from Shintoism to Christianity. Or, describing the Cuban Missile Crisis as Atheism threatening Christendom with nuclear annihilation.

In truth, both Christian and Muslim forces participated in brutality, aggression, and conquest. There were multiple causes of each engagement, including political and military motivations. The wrongs done by either side cannot be excused, but they weren't particularly savage for warfare of that era. And, as with any war, there is a significant difference between a rallying cry, and the actual motivations for the conflict. The full story of the Crusades isn't flattering to anyone involved. But it's not the cartoon of religiously-motivated evil so often leveled against Christianity.

It's especially off-base to paint the Crusades as examples of Christian bigotry and violence, or conquest. They were initially a response to centuries of Islamic military conquest, and the persecution of Christian pilgrims. The net exchange of land during the Crusades was negligible, but it did halt Muslim advances into Europe. Without that response, Islam would have blitzed its way through the continent by the middle of the second millennium. That's exactly what was happening when the first Crusade was launched, near the end of the 11th century, after more than 400 years of Islamic onslaught.

The first crusade began in 1095, as the result of several factors:

- Islamic military expansion. Muslim armies had advanced throughout the Middle East, including Jerusalem, and into Europe. They overtook much of what is now Spain, and were gradually advancing further into Europe and the Mediterranean islands.

- Religious persecution of Christians. After capturing Jerusalem, Islamic forces began to harass Christians making pilgrimages there. Too late, they realized the anger this would stir up in the West, but the damage was done.

- European military buildup. Europe had experienced decades of pseudo-peace, though armies continued to train and grow. An excess of military energy and materiel was looking for an outlet.

- Leadership tug-of-war. Popes and political rulers were vying for control of society, creating additional tension.

- Weakening Muslim leadership. After rapid expansion through violence, Islamic leaders fell into infighting and bickering. The problems caused by over-expansion created an opportunity which bolstered the early Crusaders.

The First Crusade successfully recaptured Jerusalem, and resulted in the creation of small, semi-independent "Crusader Nations" along the way. The Second Crusade began about fifty years later, after Muslim forces attacked and captured a nominally "Christian" city. This conflict was less successful on either side, and little was accomplished overall. The Third Crusade was a response to Saladin's recapture of Jerusalem. Crusaders retook a large amount of land, but settled for a truce before taking Jerusalem back.

These three major Crusades represented a full century of warfare. But, note carefully the impetus behind each one. For the first hundred years, each Crusade was launched in response to Islamic aggression. In fact, Muslims of that day would probably resent suggestions that Christians were attacking defenseless, passive people. They recognized European actions as counters to their own, and fought back in kind.

Further crusades were less popular and even less successful. Some were directly instigated by Popes, some by kings and emperors. By the Seventh Crusade, even the re-capture of Jerusalem by Islamic forces did little to stir up the European people. Both Christian and Islamic sides attacked, counter-attacked, and fortified cities. Lands were captured and lost, cities changed hands, soldiers fought and died. Little, in the end, was really accomplished, other than drawing an end line for the advance of Islamic expansion.

Tragically, both sides dealt in barbarism, which cannot and should not be excused. After Saladin was criticized for freeing Christians in exchange for bribes, for example, successive Muslim leaders took a "slash and burn" approach towards Christians for the remainder of the Crusades. Ugly as it may be, such actions were perpetrated by both sides and were common for warfare of that era.

Despite popular myths to the contrary, soldiers were not motivated to join the Crusades by plunder and power. Individual soldiers were told, in no uncertain terms, that fortune and glory were not to be expected. Men did not march to the Crusades to seek wealth, nor did their families typically cheer them on. Most who joined fully expected to die, though they were told their deaths would serve as penance for sins, and grant them favor with God. This was a direct result of Catholic propaganda, indulgences, and so forth. While religion was often used as a rallying cry, the core motivations of their political instigators, for later Crusades in particular, were the same as most other wars: land, money, power, revenge, and so forth.

Lingering impacts of the Crusades on the Islamic world were mostly psychological, and even those came long after the fighting was over. Historically, the Islamic world viewed the Crusades as an unremarkable period of war against an enemy which they generally defeated. Forces attacking from the East, such as the Mongol Empire, were considered more dangerous, and far more brutal. Almost all Arabic-language mentions of the Crusades prior to the mid-20th century are from Christian writers. Of course, specific regions experienced near-constant battle, and developed stronger anti-European sentiments which persist today.

Continue to Page Two

Image Credit: Husité - Jenský Kodex; 15th Century; Public Domain

comments powered by Disqus

Published 7-23-2014