COMPELLING TRUTH

Bible Translations

Part 1: The Issues

By Robin Schumacher

Recently I've been asked by a number of other believers my opinion on what the "best" Bible translation is, so I thought I'd cover some ground here that can hopefully be used to answer the question in the future for those who wonder about the same thing.

Honoring those who honored the Bible

The Bible has continued to be the bestselling Book year after year, and in America, we're surrounded by Bibles. That's a good and bad thing. It's good in that nearly everyone has unrestricted access to God's Word. It's bad in that we forget the costly price that great men of God paid to give us such freedom.

Some in the Church recognize the name Jerome, and know that he was commissioned by Pope Damasus I in 382 to make a revision of various old Latin translations of the Bible that existed at the time. Jerome's Vulgate was the result – an early fifth century version of the Bible in Latin.

However, Jerome's efforts didn't change the fact that the Bible still wasn't available in the language of the common people. That tide began to turn with John Wycliffe (ca. A.D. 1330-1384) who is normally credited with creating the first English translation of the entire Bible from the Vulgate.

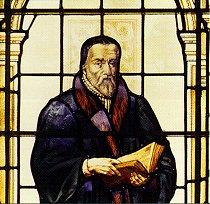

Then, a little more than a century later, William Tyndale (ca. 1492 – 1536) created the first English translation of the Bible that drew directly from the Hebrew and Greek texts. His work was also the first to benefit from the then new medium of print, which allowed for its wide distribution.

Because Tyndale's believed that the Bible belonged to everyone – and because he opposed Henry VIII's divorce on the grounds that it violated Scripture – the king had Tyndale arrested and confined to the castle of Vilvoorde, which is outside of Brussels, for over a year. Tyndale was then strangled, impaled, and burned at the stake.

Men like Wycliffe and Tyndale humble me greatly. In my study and throughout my home, I have many different Bibles. I also have Bible software on my computer, iPad, and Smartphone. If you're a Christian, maybe the same can be said of you. The next time you pick up any copy of God's Word on whatever media you happen to be using at the time, bow your head, and thank God for men like Wycliffe and Tyndale who sacrificed much so we can enjoy such easy access to the Truth.

A Jet Tour through Bible Translation Philosophies

Although some could argue there are more, I believe there to be three general philosophies or methodologies that are used to translate the Scriptures.

The first is the free translation or paraphrase approach. As its name implies, a paraphrase attempts to translate the ideas from the original text without being constrained by the original words or language. The end result is something that is very readable, but certainly not exact or true to the original texts because the author is focused on restating and either elongating or summarizing what the actual inspired texts say. An example of a popular paraphrase is Eugene Peterson's "The Message".

The next two Bible translation methods can be summarized by Friedrich Schleiermacher who wrote, "Either the translator leaves the writer alone as much as possible and moves the reader toward the writer, or he leaves the reader alone as much as possible and moves the writer toward the reader."

The second Bible translation method is the dynamic or functional equivalence approach. It does not translate by structural units or words but by "meaningful mouthfuls" or "thought by thought" with the goal being to reproduce a response in the reader that is equivalent to the response the original readers of that time would have had. The most popular example of the dynamic equivalent translation method is the New International Version (NIV).

The third Bible translation philosophy is known as either the literal equivalence method or is sometimes called the literal/formal method. It starts with a word for word translation, but will conform to the target language grammar by adding words to assist in readability. However, it still remains lexically a word-for-word or sentence-for-sentence translation. The most common literal formal translations are The King James Version (KJV) and New King James (NKJV), the New American Standard Bible (NASB), and the semi-recent English Standard Version (ESV).

Which Translation is "Best"?

I doubt any Christian would disagree on the importance of having a Bible in their hand that accurately reflects the very words God gave to the inspired writers of Scripture. Therefore, every believer should commit themselves to using a text whose goal is to accurately and faithfully communicate the meaning of the original text.

But which translation should that be?

I'll attempt to answer that question in the part two of this blog post.

Next: Part 2: A Comparison of Translation Methods

Bible Translations The Series

Part 1: The Issues

Part 2: A Comparison of Translation Methods

Part 3: What is the Best Study Bible?

Image: William Tyndale; Detail stained glass window (1911), Hertford College, University of Oxford

comments powered by Disqus

Republished 5-20-13